Are OKRs the best way to manage my Customer Experience program?

Why the nature of Customer Experience Management requires an agile and flexible way to plan and track your objectives

In Management we frequently see new concepts appear from time to time (and yes, many of those end up being empty buzzwords used to sell us stuff). New concepts, tools and methodologies that promise to fix the problems brought by the current ones. But I can assure you: OKR is not an empty buzzword, and the track history of corporations that have used them successfully, proves it.

Objectives and Key Results (also known as OKR) are not new. Even if they became notorious because of Google’s widespread implementation in the 1990’s, OKR are an evolution of Peter Drucker’s Management by Objectives (MBO) concept, that ruled the business landscape for more than 50 years.

Drucker, in The Practice of Management (1954) tells the story of three stonecutters, where the first of them thought of his work as a mean to earn his living, the second one as a way to show his professional expertise and excellence, and the third one said he was building a cathedral (as part of the whole effort). The third stonecutter was aligned with the main objective, and probably measured his progress in terms of the cathedral’s completion. But the second one was primarily motivated by his personal objectives, and that could lead him to take action in a direction that might be against the real goal.

So it became management’s responsibility to make sure everyone in the organization was working towards the business objectives, and was very clear of what those objectives were. Frameworks and methodologies arose to facilitate the implementation of the concept, and billions of dollars were spent in consulting and projects to that end. But soon it became a rigid, top-down process, where senior management fixed the objectives, and then it dripped down all the way to the front lines. Key Performance Indicators (KPI) were born as a way to measure and control the level of compliance of the objectives: monthly, quarterly, yearly, etc.

Then the world changed. Organizations needed to become faster, and recognized that much of the extremely valuable information that was collected at the front lines never reached senior management, so the objectives and strategies developed were lacking of a needed dose of reality.

This led to the rise of OKR. Andy Grove, CEO of Intel, from the 80’s to the 90’s, adapted the Management by Objectives frameworks to turn them more agile and responsive, incorporating by design the input from every layer of the organization, making it a bidirectional process, instead of a top-down one. As soon as the benefits of this new framework were known, many Silicon Valley companies begun adopting it, getting extraordinary results as well, even in the middle of the ever-changing chaos that the DotCom Bubble presented them. Key to this process was John Doerr, who learned the OKR framework directly from Andy Grove at Intel, and then became an early investor in Google, taking the framework with him as part of the board of directors. Then OKR popularity exploded.

In this article we will explore:

How OKR works? How are they different from the traditional MBO frameworks?

Why are OKR a great management approach for my Customer Experience initiatives and operations?

How is OKR different from MBO and why it works?

The OKR framework can be analyzed in two parts: the structural one (the Objectives and Key Results) and the process.

Objectives

We might have already learned the concept of Objective elsewhere. Probably we have heard about the SMART way of defining an objective: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-bound. For OKR, it is no different. When we define an Objective, it must allow us to clearly articulate what must be the outcomes we expect from it. Let’s dig a bit deeper on that. An objective is not an outcome. But it must be clear enough (Specific) to make it possible to define a set of Measurable outcomes we can expect once we Achieve it. As you might see, we have already used most of the SMART definition. Now just add the fact that any objective we set must be Relevant for the general effort, or it would be a waste of resources, and that it must happen in a constrained Time period to be useful.

Key Results

Now, how do we know we achieved the objective? We can think this from the Agile perspective of “Definition of Done”. When are we done? How do we know we were successful (or not)? Here is where we define the “Key Results”. Key Results are always tied to an Objective, and they require to be measurable and have some kind of number or tangible quality that can be evaluated. Typical Key Results take this form: “60% increase of active users by the end of the quarter”, or “Average output of 5 articles per week”. They conform a metric that can be objectively measured and compared, allowing us to know where we are with respect to the objective achievement.

Nevertheless, there is an important difference between Management by Objectives and OKR when it comes to measuring results: while MBO tends to demand strict achievement of the objective to be considered a success, OKR sets the Key Results as “Stretch Goals”. This means that when we set the desired result level in our Key Results (the numeric or measurable part of it), we set the bar high, beyond what we think it would be normally achievable. It is common to expect around 70% of the desired result, under normal circumstances. So, why to set the bar high? Because most of the time we don’t know our own potential. If we set the bar at a reasonable level, we will easily achieve the result, and probably just keep it there, even if we had the capacity for taking it further. It’s just human nature. But if we challenge ourselves, we probably will be surprised by reaching results we didn’t imagine were possible. For example, if we set a defined goal as “60% increase of active users by the end of the quarter”, we will probably get there. And nothing more. But if we know the realistic number is 60%, and we set a stretch goal as “80% increase of active users by the end of the quarter”, it is probable that the first time we attempt it, we will reach 65%. It won’t be 80%, but it will be 5% more that what we though we could achieve. That 5% wouldn’t have happened without the stretch goal.

Process

Now we know the nature of the Objectives, and the set of Key Results they must have associated. It is time to learn about the process.

We have already mentioned that a strong difference between the MBO frameworks and OKR is the rigidity that was introduced into MBO by the implementation processes that were developed over the years. A word of caution: exactly the same is happening nowadays with OKR. The original concept by Peter Drucker never had in mind for the process to be top-down and to ignore the feedback from the lower ranks (who, in the end, are the ones that deal directly with the customers and know all the truths that need to be known).

So, once you decide to implement OKR in your organization, make sure you don’t make the same mistake. Keep the process open, keep it honest, and keep everyone involved. That’s the best way to make them own the objectives, the expected results, and make them happen.

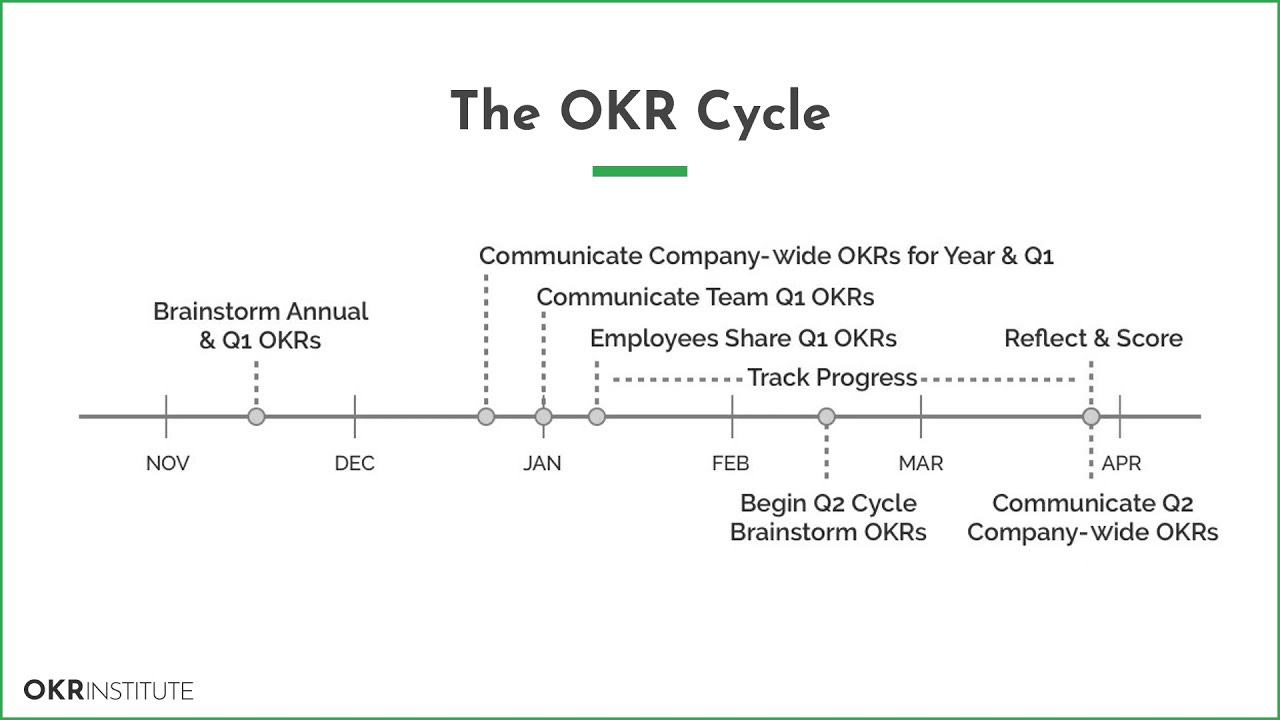

Let’s imagine a full iteration to make it easier to grasp. We are now in December, closing the current year. We have a bunch of reports from the yearly business performance, and we want to apply OKR for the first time during the next year. As senior leaders, we know what we want to achieve next year. We might want to launch new products, or increase the marketshare of the ones we already have, or a combination of it, for example. We know our current numbers: our production capacity, our marketing budget, etc. So, we set a number of stretch objectives. Between three and five. No more (where three is better than five). And we define their Key Results, following the guidelines we already mentioned: measurable, time-bound, achievable but challenging, etc.

Leading and Lagging Indicators

Let’s stop for a moment to discuss an additional tip for developing Key Results. It’s almost sure you have heard about “indicators”. But it’s not as certain that you have heard the difference between Leading Indicators and Lagging Indicators. Without going into much detail, because it is a topic that will have its own article, lagging indicators are measured at the end, when you want to know if you achieved the objective or not, while leading indicators measure the steps you take during the process, so you can steer your performance and make sure you meet the goal. Having only lagging indicators is a sure way to find out you failed, and not having anything else to do about it. Associated leading indicators can help you save your objective while there is still time.

The nature of leading vs lagging indicators is the reason why I recommend to have them at least in pairs when we define our Key Results. We want to have a lagging indicator, that measures if we accomplished the stretch goal. But we also need associated leading indicators that help us move through the quarter adjusting what we are doing until the projected result is satisfactory.

Back to the Process

Ok, back to the Process. Now that we have the Organizational OKRs, we need to show them to the whole company. Because yes, OKRs must be public, and we will see soon why.

Remember, this is important: this is not a top-down process. You are not the evil overlord mandating on your minions the Objectives and Key Results you have masterfully crafted. You are presenting them to everyone so each department can take them as a starting point to try to develop their own set of OKRs (Department or Business Unit OKRs). They might question the feasibility of some of the Organizational Key Results, or even the Objectives. You must be prepared to answer why you considered those as attainable. Or they might bring valid objections that might force you to adjust them. That’s the whole idea. They know operational things that you don’t, and that can have an impact on whether an OKR makes sense or not.

Once the discussion over the Organizational OKRs is over, it is time for the Business Units or Departments to develop their own. This is also a public process. The reason is that rarely an objective is something a department can achieve on its own, or won’t affect another department. So, if I need help from someone, I need to let them know so they include our request in their planning, as this affects their total capacity. And the same in the other direction: we must account for the work we are helping achieve others, as part of our plans.

Departamental OKRs must be fully aligned to the Business OKRs, and must explicitly state how each Departamental Objective supports the achievement of one or more of the Business Key Results (and its associated Objective). And also must be aligned between Departments, making sure everyone knows what we need from them and we know what everyone else needs from us. This is an iterative process where everyone in the Department must participate, because once the Departmental OKRs are settled, each individual must elaborate their Personal OKRs, where the process is the same: fully align them to the Departamental OKRs, and with each other individual, to make sure everything is accounted for.

Once the OKRs are considered finished, the teams meet again to present them to everyone (not only upper management), so everyone must agree on them. This has been a collaborative effort, so there shouldn’t be any surprises, but this is the perfect moment to catch them if they exist. If any fixes are needed, they are noted, and the OKR planning process is over for the quarter.

Then, work starts and everyone keeps public their progress on their respective Key Results. And around mid-quarter the organization meets again so each department can show their current progress, and assess if they will be able to meet or exceed the proposed Key Results, and what this means to the achievement of the objective. It is very important to keep this meeting honest and constructive, because hiding information might impact the results not only of one department, but others that depend on it.

Finally, before the quarter ends, the organization meets again to start the development of the draft Q2 OKRs and to reflect on the Q1 OKRs, so any mistakes made can be avoided during the Q2 process.

At the beginning of the Q2, the final grading of the Q1 OKRs is made (this is also a public event, with everyone attending) the results of the retrospective are mentioned so everyone can learn from them, and the Q2 OKR planning continues in the same fashion as the Q1 one.

Why are OKRs a great management approach for my Customer Experience initiatives and operations?

So far, we have reviewed how OKRs work, and their main differences when compared to Management by Objectives. But something that might not be evident is the flexibility that OKRs introduce by planning quarterly, in an iterative fashion over the year, while incorporating lessons learned from the previous iteration and the feedback from the whole organization. Quoting Dwight Eisenhower: “In preparing for battle I have always found that plans are useless but planning is indispensable”, it should be obvious that under a volatile and uncertain environment like today’s, it’s almost sure we will have to adapt our plans (and a lot). OKRs brings us a clear process and the needed artifacts to do that.

Customer Experience initiatives require a lot of trial and error. It is a deep Cultural Change, and what works for one organization not necessarily will work for another. There are no magic recipes. So it needs to be addressed in an experimental way, permanently adjusting the organization to achieve Continuous Improvement. OKRs are the perfect management framework to accomplish this. The fact that OKRs are built both top-down and from the bottom-up means that the knowledge the front line personnel have of the Customer will be part of the strategy, planning and metrics developed by the organization, avoiding the typical problem of disconnection from reality that afflicts senior management.

Where do I begin?

By reading this article you have taken the first step in the right direction. You can start doing some research on OKRs on your own, so you become familiar with the framework, and perhaps start implementing it in your organization. I really recommend the book Objectives and Key Results: Driving Focus, Alignment and Engagement with OKRs from Paul R. Niven and Ben Lamorte (Amazon link here1). Check my previous article on Customer Experience Strategy2, if you need some ideas on what you will need to do to implement your own Customer Experience program. And, of course, you can join my newsletter and Facebook Group to keep in touch and receive additional information. If you have any comments or suggestions, don’t hesitate to let me know in the comments section.

When you are ready, here is how I can help:

“Ready yourself for the Future” - Check my FREE instructional video (if you haven’t already)

If you think Artificial Intelligence, Cryptocurrencies, Robotics, etc. will cause businesses go belly up in the next few years… you are right.

Read my FREE guide “7 New Technologies that can wreck your Business like Netflix wrecked Blockbuster” and learn which technologies you must be prepared to adopt, or risk joining Blockbuster, Kodak and the horse carriage into the Ancient History books.

References

Objectives and Key Results: Driving Focus, Alignment, and Engagement with OKRs (Wiley Corporate F&A) 1st Edition, Kindle Edition

https://www.amazon.com/Objectives-Key-Results-Alignment-Engagement-ebook/dp/B01LYHKS6V

Transforming the Customer Experience

https://alfredozorrilla.substack.com/p/transforming-the-customer-experience